Titan – The Only other World with Active Weather

Titan is unique in the solar system in that carbon, water, and energy – typically taken as the requirements for life – are interacting on the surface today. Also remarkable is that, when we look across Titan’s surface, we see landforms that bear a striking resemblance to those we find on Earth.

If one were to land near Titan’s polar regions, you would find hundreds of small lakes and vast hydrocarbon seas. These smaller lakes (which we have termed “sharp-edged depressions”) look in part to be formed by a type of collapse mechanism, yet they also retain massive raised rims around their perimeters that make them unlike anything we have observed on the Earth. The larger seas, meanwhile, are truly impressive, larger in area than any of Earth’s large lakes! These seas also look like they have flooded pre-existing high-standing topography, evidencing that Titan’s climate is actively changing.

At the equator, you would find an entirely different planet. Nearly wrapping around the entire globe, Titan’s organic linear dunes are 100’s of meters tall, and embay nearly everything. You would also find alluvial fans draining off of Titan’s water ice mountains, and almost all of Titan’s impact craters, sparse as they are. These low latitudes then appear like a vast desert, presenting quite the dichotomy with the humid, hydrologically-rich poles. It is pretty clear to me (and hopefully others!) that Titan is unlike any other known world, one that remains the place to go for studying both Earth-like surface processes.

Why care about Titan?

What’s most exciting to me about Titan is that, outside Earth, Titan has the only other active planetary hydrologic cycle. Whereas Mars once was active, little has happened for billions of years, and much of the record has been lost. Not to denigrate Mars, but the place to study planetary hydrology is clearly Titan, it is active right now!

What makes Titan even more interesting is that, while everything “looks” familiar, everything about the Titan environment is completely different from Earth. Instead of water, Titan’s rain, rivers, and seas are liquid methane and ethane with dissolved atmospheric nitrogen, the volume of which is highly sensitive to temperature, pressure, and methane-ethane composition. These properties lead to dynamic and significant (up to 50%) variations in a river’s density and viscosity that can vary both across a drainage basin and where methane rivers interface with methane-ethane seas. Also, Titan’s solids are not silicates or carbonates, the properties of which are very familiar to anyone who has ever picked up a rock. Though we don’t know for sure (yet), Titan’s “rocks” are likely some combination of water ice (which makes up its lithosphere) and organic solids precipitated from the atmosphere itself, possibly forming entirely new minerals.

And perhaps most exciting of all is that, while Titan is far from the Sun and lacking as much energy as Earth to drive climatic processes, it is the sluggishness of Titan’s thick atmosphere that may have some truly fascinating implications! Imagine a typical large storm on Earth: it occurs roughly once per year, and lasts for about a day. If you go out to the landscape after such a storm, you would easily observe the effects of floods, strong winds, etc. Now imagine that such storms occur every 7 years (or twice per Titan summer if you live on Titan), but the storms last for months! The effect that such massive storms have on the landscape will be way different than Earth, challenging our understanding of basic concepts like the “bankfull” flood.

As the cherry on top, Titan also lacks the complex interplay of diverse physical and chemical processes – including active tectonics, diverse climate zones, vegetation, and humans. This means Titan is a rather simple environment, one that can isolate for us the basic fundamentals of how climate influences the evolution of landscapes. So, while Mars is really cool, I think that we need to continue to explore Titan with as much vigor, as it provides a truly unmatched opportunity to study the fundamentals of all the processes so familiar to us on Earth!

Where are do we go next with Titan?

While Cassini ended its mission in spectacular fashion in 2017, its datasets will be dissected for decades to come as there is still much to be learned. Laboratory experiments are also a terrific avenue to persue, as we can approximate the Titan environment using analog experiments. Finally, numerical experiments can be a useful tool for exploring how Titan’s climate and landscapes are coupled, though they should be used with caution given our still primitive understanding of Titan’s materials. My research on Titan leverages all these different, complementary techniques.

One question that has caught my attention lately is why, unlike many coastal rivers on Earth, most of Titan’s rivers do not terminate in deltas. Titan has liquid filled seas, we know it rains, we see kilometer-scale rivers intersect with the shorelines, yet we see only one river that has a delta at its terminus. Why?

Possible solutions to the question of Titan’s missing deltas fall into two main categories: (1) deltas like those we see on Earth do not form (or rarely form) on Titan because of differences in materials, dynamics, and coastal conditions between the two worlds, or (2) there are many deltas on Titan, but the characteristics of the deltas and of Cassini datasets make them difficult to identify – Titan’s deltas may simply “look” different. Deciphering between these two end-members has captured much of my attention these days, and is the focus of my postdoc at MIT.

We have begun deciphering between these two end-members through a series of different theoretical, experimental and numerical investigations. To study the dynamics of sediment transport within a Titan river, we have developed analytic expressions based on the concept of hydraulic geometry. This new work, currently under review, has produced some fascinating results that have implications for rivers not only on Titan, but on Mars and Earth too! We also developed a nifty numerical model that simulates the appearance of deltas as Cassini would see them on Titan, which we are now using in our ongoing search through Cassini data for deltaic and coastal features. Once these studies are all done, we can couple our numerical model with the output of upcoming laboratory plume experiments. These experiments should be a lot of fun, and will launch follow-up investigations into river plume behaviors as we change variables like: the density contrast between the river plume and the ambient fluid, gravitational acceleration, basin slope, and river discharge. Are there new dynamics that may be at play on Titan that we haven’t had to think about, such as fingering instabilities when less viscous (methane) river enters a more viscous (methane-ethane) sea, or nitrogen bubbling? So, through all these studies, hopefully in the next couple years we can finally understand what happened to Titan’s deltas!

Beyond these missing deltas, Titan’s similarity to Earth poses many additional questions. For example, during the Pre-Cambrian period here on Earth, most of Earth’s rivers were thought to be braided. Only with the rise of vegetation did single-thread channels arise, as mud was able to form through a process called “flocculation,” adding cohesion to the banks of rivers. Titan has no vegetation, so does it have single thread rivers? If so, what analogous process creates “mud” out of Titan’s materials? If not, that means Titan’s rivers are reflective of the rivers that evolved Earth’s landscapes for the first 90% of its life! Deposits from these rivers on Earth are extremely rare, yet they may be sitting there on Titan today, waiting for us to study them, giving us a window into our own past!

Another big question is whether Titan’s atmosphere has been around for billions of years, or whether it is very young, having been outgassed only in the last few million years. Fortunately, we can use Titan’s landscapes to answer this question! If the atmosphere turns out to be ancient, then there must be an additional thermostat, outside the carbonate-silicate cycle that regulates Earth’s climate, that can stabilize planetary climates!

As we learn more about Titan’s climate, we can also use its landscapes to understand what the impacts of these months-long, years apart storms are. The famous Woman & Miller study in the 1950’s gave rise to this concept of a “bankfull” discharge, where they postulated that there was a sweet spot between events large enough to shape landscapes, but frequent enough to do significant work. On Earth, this ended up being the 1-2 year flood, but why that is remains up for debate. What is the relevant magnitude and frequency of storms on Titan, and what are the implications of this?

Titan’s seas also provide us the opportunity to apply oceanographic techniques to understand how fluids move within the seas and how they shape the shorelines. With a fluid that has a large temperature-dependence on its density and viscosity, could circulation be driven by evaporation/precipitation alone? Could this be acting in addition to waves and tides to equilibrate the composition of the seas? Or do you need to sequester methane into the subsurface? Numerical and analytical modeling of sea circulation could therefore unveil to us what is setting the composition of Titan’s largest liquid reservoirs.

And of course, there are so many other questions we will be asking over the next couple years and decades. But Cassini has its limitations, and laboratory and numerical experiments can only be so useful. More data is always needed!

Fortunately, a new mission is on the near horizon! Dragonfly, a mobile (aerial) lander, was selected by the New Frontiers 4 program in 2019, and is now under development at the Applied Physics Laboratory (APL). Nominally, it will land at the Selk impact crater near Titan’s equator in the mid-2030’s. Once safely on the surface, it will begin its hunt for prebiotic chemical processes that may be precursors to life, by searching for locations where impact melt (i.e. liquid water) was in contact with organics. Fortunately, that isn’t all Dragonfly can do! Making multiple flights, Dragonfly, will also measure the surface properties of Titan’s dunes and impact ejecta, and make measurements of any rivers, hillslopes, and fluvial deposits it encounters along the way. With an in situ, well-equipped platform, our understanding of Titan surface and climate science will take enormous strides forward!

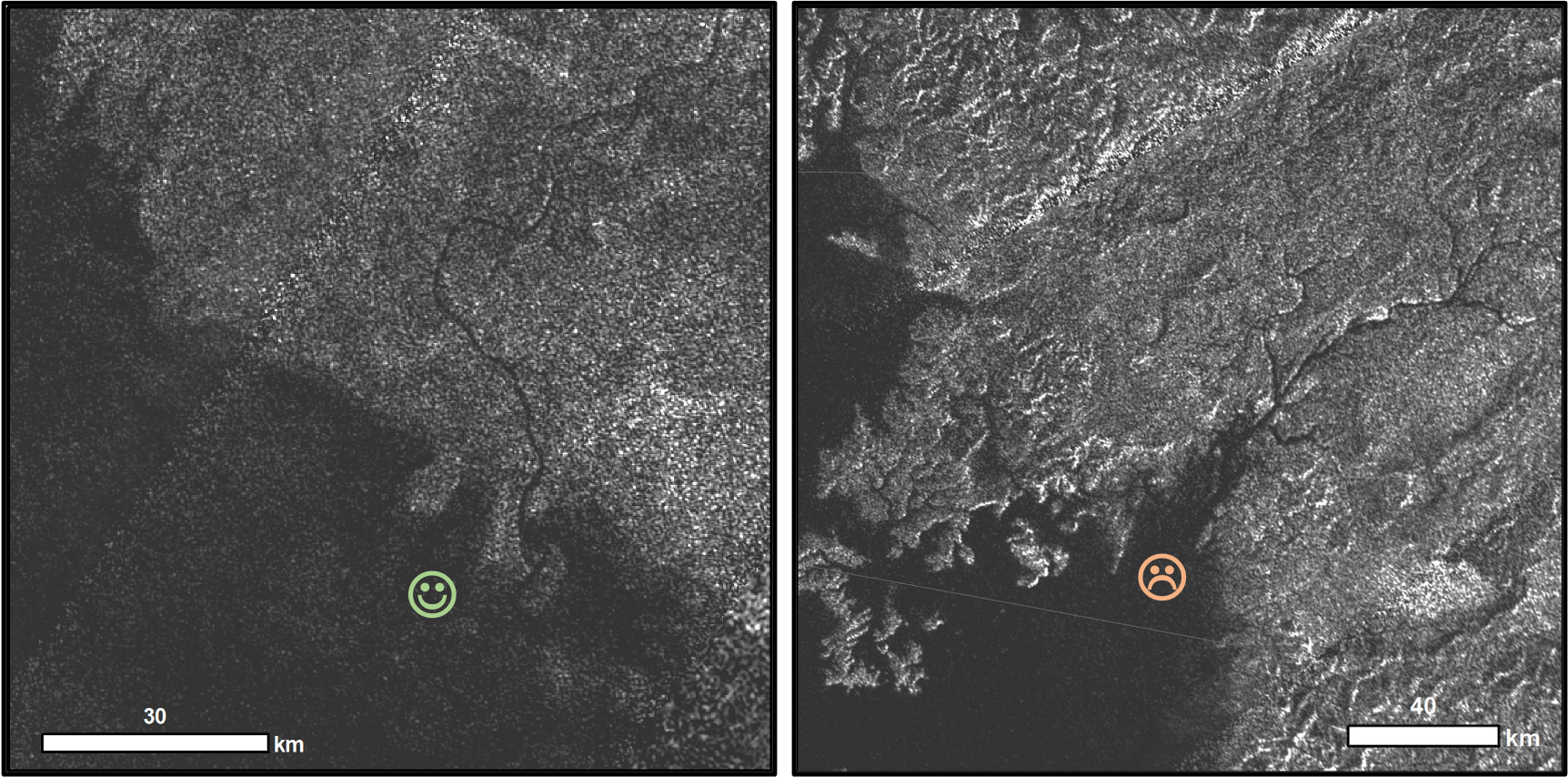

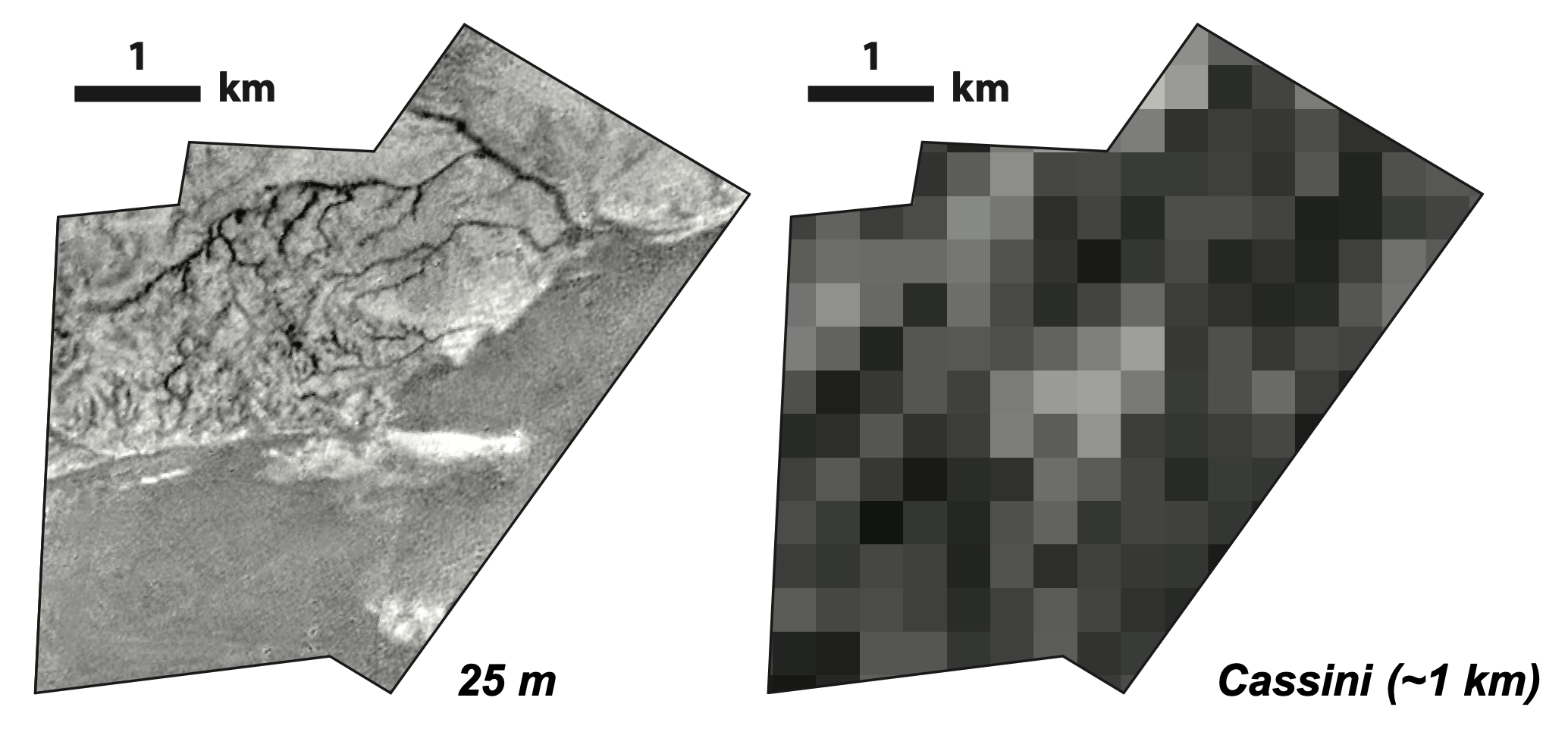

And hopefully it doesn’t end with just Dragonfly! A terrific opportunity exists, in the coming decades, to go back to Titan a second time with an orbiter, something prioritized in the 2023 Decadal Survey. Simply, we are in a similar state to what Mars surface science was in the 1970’s after the Mariner missions, where surface features <1-kilometer in size were not resolved and topography was generally absent. Just as the Mars Global Surveyor changed our understanding of Mars, global topographic data and a factor of ~30 increase in image resolution offered by an orbiter would radically change our understanding of the entire Titan system. Yet, unlike Mars, I’ll remind you that Titan is active today! And so we could watch its dunes evolve, see how beaches around its seas migrate during these large storms, and look for river plumes as they enter the seas. Only at the Earth can we watch such processes, and so I cannot wait for the day when we can do the same with Earth’s most similar planetary sibling!

Mars – An Ancient Hydrologic System

Work in progress, check back soon 🙂